Criminal justice

Contents

Addressing late disclosure of evidence - High Court criminal disclosure practice note

The impact of parental incarceration on children

District Court | Te Kōti-ā-Rohe

Judicial officers in the District Court

Te Ao Mārama - Enhancing justice for all

Local solutions to local conditions: The District Court Local Solutions Framework

Jury trials in the District Court: Cases heard, cases resolved

Remand prisoners: Why delays matter to those remanded in custody awaiting trial or sentencing

| Previous section: Courts of general jurisdiction | Next section: Civil justice |

Criminal justice proceedings make up most of the work of New Zealand’s courts. Criminal trials are heard in the District Court, Youth Court and High Court.[26] Appeals for criminal cases are heard in the appellate courts—the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal and the High Court— see also “Appellate Courts”.

High Court | Te Kōti Matua

The High Court deals with the most serious criminal cases including murder, manslaughter, attempted murder, and serious sexual, drug and violent offending. It conducts all sentencings in which preventive detention is a possible outcome. The High Court also hears protocol cases,[27] and appeals from judge-alone trials in the District Court and Youth Court. It does not hear appeals from District Court jury trials. See “Appellate Courts” for more on the High Court’s appellate jurisdiction.

This year, the High Court cleared all rescheduled COVID-19 criminal jury trials, which meant that jury trial numbers returned to pre-pandemic levels. However, delay remains a concern for the Court. In the High Court, there are several contributing factors to delay. For instance, the nature of the cases making up the court’s workload has a significant impact. The average time required for a trial has increased as a result of more complex matters coming before the Court, such as offences involving multiple defendants. There are also more homicide and attempted murder cases coming before the Court. These cases must be heard in the High Court and they now make up the majority of the High Court’s criminal workload.[28]

In some parts of the country, there is a lack of appropriate courtrooms in which to hold criminal jury trials.[29]

Other factors that contribute to delay reflect the complexity of our justice system, with solutions requiring co-operation across the justice sector. One such example of a cross-sector issue is late disclosure of evidence, discussed below. Other factors reflect shortages of resourcing in agencies that support the courts. Many hearings, particularly sentencing, require specialist health assessor reports from psychiatrists or psychologists. There is both a shortage of skilled report writers in New Zealand, and a high demand for the reports—around 91 percent of people in custody have a diagnosis over their lifetime of either a substance abuse or mental health disorder, and around 60 percent meet the diagnostic criteria within the 12 months prior to their imprisonment.

The issue of delay is explored further under “Timely and accessible justice”.

Addressing late disclosure of evidence - High Court criminal disclosure practice note

Late disclosure of evidence causes delay in criminal cases in the High Court. When evidence is disclosed late, it puts pressure on counsel and can result in trials being adjourned.

In March, the Chief High Court Judge Justice Susan Thomas issued the Criminal Disclosure in High Court Trials Practice Note, which requires the Crown and defence to actively address disclosure issues at an early stage to avoid delays caused by late disclosure. This is discussed further under “Timely and accessible justice.”

The impact of parental incarceration on children

Children’s life trajectories are dramatically altered when a parent or caregiver is sent to prison, even for a short time. They can lose their homes, their schools, their security. It is important that judges know of a defendant’s caregiving responsibilities before sentence or remand. A webinar to discuss this was held in October by Chief High Court Judge Justice Susan Thomas and leaders of the legal profession Fiona Guy Kidd KC and Stacey Shortall. It was attended by over 600 lawyers.

The initiative was in part a response to the independent review by Dame Dr Karen Poutasi following the murder of 5-year-old Malachi Subecz by his carer while his mother was remanded in custody.[30]

The webinar aimed to increase practitioners’ awareness of the impact upon children when their parents are incarcerated, whether following charge, bail hearings or sentencing. Practitioners were encouraged to ensure judges were aware of the nature of their client’s caregiving responsibilities, so that they can be considered in the judge’s deliberations. The session drew on experiences in Aotearoa, as well as British research, and in particular the work of Dr Shona Minson.

The Office of the Chief High Court Judge and the Office of the Chief Justice worked with the New Zealand Law Society to produce the webinar, which was funded by the Ministry of Justice.

The webinar and supporting materials can be accessed on the New Zealand Law Society’s Continuing Legal Education website.[31]

The judiciary continues to work with other agencies to ensure that systems within justice agencies promote the provision of information to judges, and to ensure that the effects on children of the criminal justice system remain in focus.

District Court | Te Kōti-ā-Rohe

Every person in New Zealand who is charged with a criminal offence makes their first appearance in the District Court, even if their charge is ultimately heard in the High Court. In a typical year, more than 105,000 new criminal cases enter the District Court.

Although the number of new cases in the court has been decreasing, as with the High Court, cases are taking longer to resolve. In the District Court, the contributing factors include: an increase in the number of serious and complex Category 3 cases before the courts;[32] more defendants electing a trial by jury, instead of by a judge; and defendants entering guilty pleas later in the court process. The extra court events needed before a late guilty plea is entered increase the workload of the Court.

Initiatives that the District Court is leading and collaborating on to address delay are covered in detail under “Timely and accessible justice”.

Judicial officers in the District Court

In addition to District Court judges with general or jury warrants, community magistrates and judicial justices of the peace (JJPs) also play an important role in carrying out District Court criminal work. Community magistrates generally sit in urban courts and preside over a wide range of less serious criminal cases. JJPs preside over some preliminary hearings and bail applications. They hear and sentence in minor cases.

There are 20 community magistrates located in nine courthouses, and more than 170 JJPs who sit nationwide.

Te Ao Mārama - Enhancing justice for all

Te Ao Mārama (the world of light) is the new operating model being developed by the District Court. It has two main goals—to support fair hearings by ensuring full participation of all parties, and to address root causes of offending by facilitating community and government agency involvement with defendants and their whānau, with a view to ensuring better long- term outcomes for offenders and the community.

Te Ao Mārama pulls together the best practice, solution-focused judging principles that have been developed in the Youth Court and specialist courts within the District Court over the course of 40 years. These courts have developed programmes that provide wrap-around support for people going through the court process.

They have enabled defendants to access support to address the causes of their offending—for example, addiction, homelessness and challenges with literacy—and provided ongoing judicial oversight to ensure participation.

Resource constraints meant that many of these solution-focused courts are only available to people living in certain locations—for example, the Young Adult List Court in Porirua, Gisborne and Hamilton, the Matariki Court in Kaikohe, the Court of Special Circumstances in Wellington, and the Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment Court in Auckland, Waitakere and Hamilton. This leads to the possibility of “postcode justice”—that a defendant will receive a different outcome and different opportunities depending on where they live. This prospect is contrary to the rule of law, which requires that all people will be treated equally under the law.

The Te Ao Mārama Best Practice Framework draws together for the first-time best practice from these solution-focused courts to be applied in all District Court locations in order to spread the benefit of lessons learned in solution-focused courts. It was published in December and resources will be developed to support courts.

Te Ao Mārama is progressively being implemented in the family, youth and criminal jurisdictions in eight District Court locations (Kaitāia, Kaikohe, Whangārei, Hamilton, Tauranga, Gisborne, Napier and Hastings), with funding to support development of community-based service provision in the Court. Other locations are adopting elements of the framework relevant to the work of the Court and their local community, as funding allows.

The Te Ao Mārama framework is not “one size fits all” and may look different in each location depending on local needs. It reflects the communities it serves, including whānau, people with disabilities, Pacific peoples, Rainbow communities, and refugee and migrant communities. There is a focus on ensuring it is effective for Māori given the disproportionate representation of Māori in the family violence, care and protection and criminal jurisdictions of the District Court.

Timely justice is a central feature of Te Ao Mārama, which recognises that every court appearance must be meaningful to participants and aims to reduce unnecessary adjournments.

Te Ao Mārama approaches we already know work well include the following:

- creating connections with local communities

- improving the quality of information judicial officers get to inform their decisions

- improving processes for victims and complainants

- encouraging people to feel heard in the courtroom

- establishing alternative courtroom layouts

- using plain language

- reducing formality.

Te Ao Mārama is especially focused on supporting at-risk children and families when they are engaging with the family and criminal justice systems. It has significant potential to reduce the number of children in care, the number of children who offend in the medium term, and the number of young people who enter the adult criminal jurisdiction in the longer term— all contributing to an enduring reduction in offending and reoffending and the costs of crime.

Te Ao Mārama will operate within the framework of existing legislation including the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990, the Bail Act 2000 and the Sentencing Act 2002. It does not require any new legislation. It will be given effect through new behaviours, new information, new services and new processes across both the criminal and civil jurisdictions.

Local solutions to local conditions: The District Court Local Solutions Framework

When local conditions (such as illness of staff or other participants) prevent a court from dealing with its normal workload, a local solutions framework operates to ensure that the requirements of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990 are observed and that issues are prioritised, with time-critical proceedings and those that affect life, liberty, wellbeing and personal safety being given the highest priority. Courts only resort to a local solutions framework when business as usual is not possible.

The framework, originally developed in response to the challenges of operating under COVID-19 restrictions, sets out the priority order in which proceedings will be scheduled and conducted, and the way in which they will be heard— for example, using remote technology if required. It has proven an invaluable tool for the District Court and was used to ensure court operations continued to the greatest extent possible as court repairs took place following the Auckland Anniversary floods and Cyclone Gabrielle.

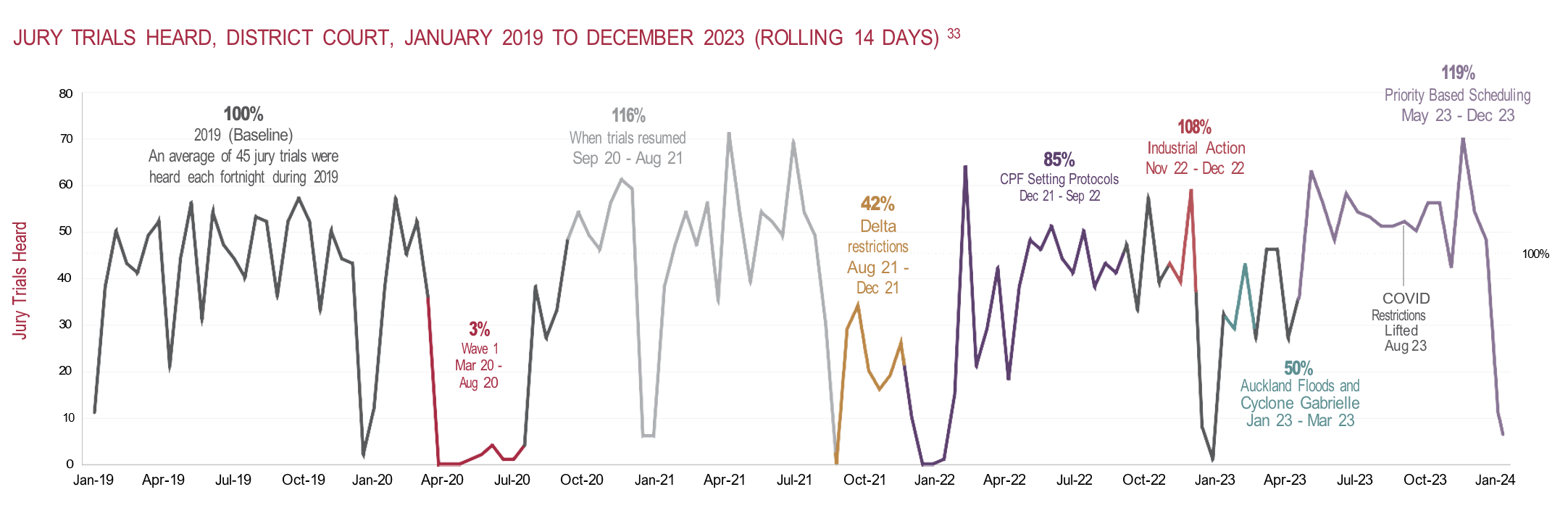

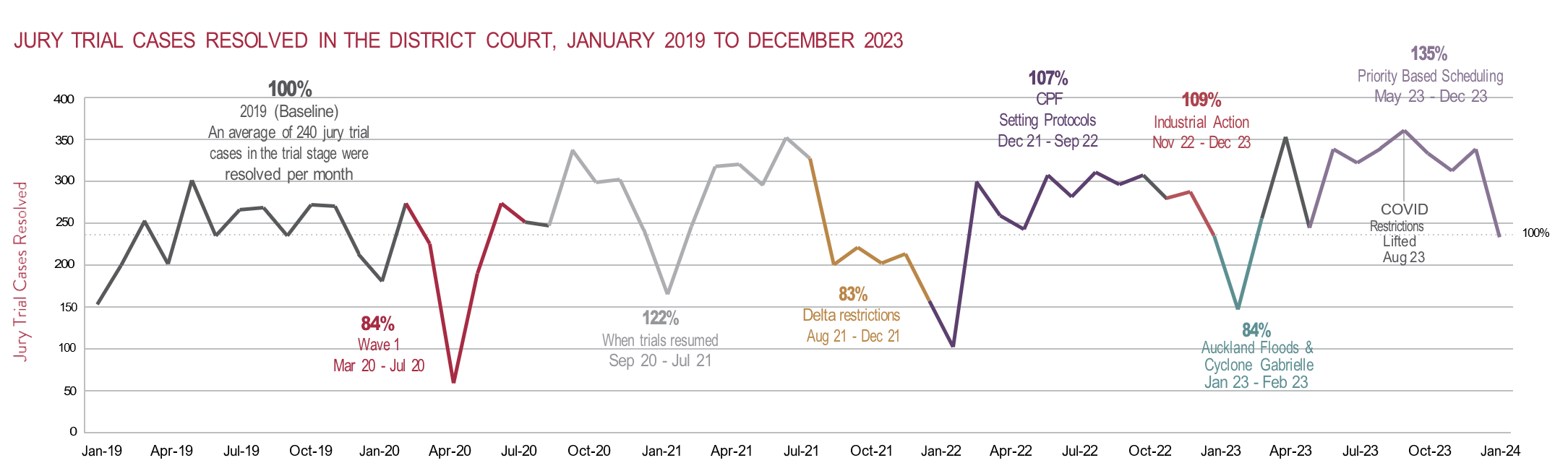

Jury trials in the District Court: Cases heard, cases resolved

Set against a 2019 baseline, these graphs show how the number of jury trials held and resolved was affected by external influences, such as COVID-19 restrictions, extreme weather and the actions of the judiciary, such as the introduction of priority scheduling.

The following graph shows how the number of jury trials held:

Notes: [33]

- Includes jury trial hearing events on cases in the District Court.

- Includes events with an event status of complete, including mistrial and settled prior.

- Only one event is counted for each case.

- The Christmas holiday period is not included in the above calculations.

- Data is based on the Court's Case Management System as at 10 April 2024.

The following graph shows how the number of jury trials resolved:

Notes:

- Includes cases on the Jury Trial track in the District Court.

- “Jury Trial Cases Resolved” includes all cases at trial stage that were disposed. This includes disposals through a hearing, a guilty plea before or on a jury trial hearing, or other. Some of these cases may still be awaiting sentencing.

- This is monthly data, and all figures are monthly averages over the entirety of the months in each stated period. As such, public holidays including the Christmas holiday period are included in the above calculations.

- Data is based on the Court's Case Management System as at 4 April 2024.

Remand prisoners: Why delays matter to those remanded in custody awaiting trial or sentencing

Delays for remand prisoners are problematic. Research shows that spending even a short period on remand in custody has significant impacts on a defendant's life outside of prison—such as the loss of employment and housing.

A defendant’s whānau is also affected. There can be significant and long-lasting impacts on young dependent children separated from their caregivers. See "The impact of parental incarceration on children".

Some remand prisoners will not be convicted once they come to trial, yet will have already spent time, perhaps long periods of time, in prison. Others will be convicted but will receive non-custodial sentences, or sentences that are shorter than their time already spent on remand.

Prisoners on remand do not have access to rehabilitation. Those who are convicted might therefore be released before they have had opportunities to address the causes of their offending.

|

Youth Court | Te Kōti Taiohi

The Youth Court is a specialist division of the District Court and deals primarily with offending by young people aged 14 to 17 years. In certain circumstances, the Youth Court also deals with serious offending by children aged 12 to 13 years. Some serious offending by 17-year-olds is transferred to the adult criminal division of the District Court. Any child or young person charged with murder or manslaughter is dealt with by the High Court.

There are 61 permanent judges holding a Youth Court designation and 14 acting warranted judges.

The Youth Court is led by Principal Youth Court Judge Ida Malosi. The Court is highly regarded internationally for its innovation and solution-focused judging.

Most young offenders are diverted away from formal court interventions and dealt with by Police Youth Aid officers. This means that the young people in the Youth Court are the most serious offenders. They come to the Court with a complex range of issues such as severe trauma, neurodiversity, mental distress, addiction and disengagement from education.

The Oranga Tamariki Act 1989, which created the Youth Court, draws upon tikanga Māori concepts. It emphasises the engagement of whānau to address a young person’s conduct and uses restorative justice principles to support the victim and bring home to the young person the consequences of their offending.

A unique feature of the Youth Court process is the family group conference, which involves a gathering of the young person, their family, victim(s), Police Youth Aid, the young person’s youth advocate (lawyer) and other professionals. The parties establish a plan to address the offending and underlying causes, provide for victims’ interests and help the young person take responsibility for their actions.

Another unique feature is that in some circumstances, the Court can deal with care and protection and youth justice issues at the same time, presided over by a judge who holds a Family Court warrant and Youth Court designation.

Not all Youth Court proceedings take place in a traditional courtroom. Te Kōti Rangatahi | Rangatahi Courts and Pasifika Courts are held at marae or community venues and Māori or Pasifika customs, and cultural practices are used as part of the court process.

There are 16 Te Kōti Rangatahi nationwide and two Pasifika Courts based in Auckland—in Waitakere and Manukau. These courts were established to address the over-representation of Māori and Pasifika in the youth justice system.

Trends in youth justice

It was a challenging year across the youth justice sector. Ram raids and other serious retail crime were a persistent issue. The Youth Court handled more cases in 2023 than in any of the previous five years, with the biggest increases in the Auckland Metro region and Canterbury.

Despite the rise in cases this year, it is important to note that there has been a rapid and significant decline in the numbers of young people in the youth justice system since the Court first began work in 1989. That year, approximately 10,000 cases involving children and young people appeared before the Court. Some 35 years later, with almost two million more people in New Zealand (from 3.3 million to approximately 5.2 million) the total number of cases that flowed into the court in 2023 was around 4,500, and at the end of the year there were 1,071 active cases being monitored by a judge or awaiting a hearing.[35] This is despite an increase in the court’s jurisdiction – in 2019, 17-year-olds were included in the Youth Court jurisdiction. This sustained reduction is the achievement of an evidence-based, system-wide response to youth offending and restorative justice.

| Previous section: Courts of general jurisdiction | Next section: Civil justice |

Footnotes

[26] Criminal trials for military officers and staff are heard in the Court Martial.

[27] Protocol cases involve serious or complex offending. In accordance with the Criminal Procedure Act 2011, a High Court judge makes the decision as to whether the case is tried in the High Court or District Court, in accordance with the protocol. The protocol is used to ensure both that cases are heard in the most appropriate court and also to manage the workload between the District Court and High Court.

[28] In the Auckland High Court, in 2018, 33 percent of the Court’s criminal workload was category 4 offences; by 2023, that had risen to 78 percent.

[29] For example, there is only one courtroom available to the High Court in each of Whangārei and Rotorua.

[30] Independent Review of the Children’s System Response to Abuse | Oranga Tamariki—Ministry for Children.

[31] Impact of Parental Incarceration on Children webinar, October 2023.

[32] Category 3 offences are offences with a maximum penalty of a prison term of two years or more (excluding Category 4 offences).

[33] Please note that the Jury Trials Heard chart from the Chief Justice's 2022 Annual Report (page 30) contained a data error leading to an undercount of trials heard across the period and showing that the number of jury trials heard in the latter half of 2022 was only ~50% of the 2019 Revised data shows that the number of jury trials heard had, in fact, bounced back up to 2019 levels by mid-2022.

[34] The data for 2021 and 2022 has been updated since the publication of the Chief Justice’s Annual Report 2022. The updated figures are presented here.

[35] The figure includes all active cases at any step of the process— administrative, charges denied, defended and monitoring.